A sermon prepared for the Third Sunday in Lent, March 15, 2020, by Christopher L. Webber

The first ecumenical discussion group met beside a well in Samaria almost 2000 years ago. Jews and Samaritans had been separated for about 500 years – about as long as Lutherans and Episcopalians and Roman Catholics. Like Christians today, they both had the same basic Bible, they both traced their descent from Abraham. But those who were called Jews had been through a 70-year period of exile in Babylon during which time the way they expressed their faith had been radically changed. The exiled Jews had added to the Bible and they now insisted that worship had to be centered in Jerusalem. No wonder the Samaritans weren’t prepared to go along. It’s not too different from the way non-Roman Catholics object to what seems to them additions to Biblical teaching and the new idea that everything has to be centered in Rome.

Even so, it was probably more a matter of class that divided them since the Babylonians had taken only the leadership group into captivity and the Samaritans were those who had been left behind, the so-called “people of the land,” the farmers, the blue-collar workers, the people least likely to cause trouble for the Babylonian occupation troops. In a similar way, there were economic issues in the Reformation that may have been more important than the theological issues. Christians in the north of Europe, for example, objected to the way their tax money went south to build St. Peter’s when they could have used that money to improve their own conditions. So at any rate there were all these issues dividing Jews and Samaritans and they basically didn’t talk to each other.

Of course, Jesus was different. He told a story, you remember, about a Samaritan who was a better neighbor to a wounded Jew than the Jewish leaders who went on by. And now he sits down beside a well and begins a conversation with – not just a Samaritan – but a woman. A Jewish man  shouldn’t have done that. But Jesus had this idea that people should love one another, that divisions should be broken down, that people should come together and work together. So he ignores all the taboos, the prejudices, the traditions, and starts a conversation.

shouldn’t have done that. But Jesus had this idea that people should love one another, that divisions should be broken down, that people should come together and work together. So he ignores all the taboos, the prejudices, the traditions, and starts a conversation.

The Gospel tells us that the disciples had gone away to buy food so they weren’t there to check up on what Jesus was doing. It tells us that when they came back “they were astonished.” You bet they were. What if the Secret Service reported for duty some morning during a presidential trip to the mid-East and found the president deep in conversation with somebody in a turban? Some things you just don’t expect.

But what I want you to notice is how Jesus begins this conversation. He asks for help. “Please give me a drink.” Bad enough he’s talking with a woman of an alien sect, but he asks her to help him. The disciples would rather have died of thirst. But I said this was the first ecumenical discussion group, and if you want to break down barriers, there’s no better way to start than to admit that the other has something you need. You and I know that we have what Roman Catholics need: the freedom to use our minds and make decisions that seem right to us without waiting for word to come down from Rome. But if we set out with that attitude, we won’t get very far. “Look, my way is better than your way; let me show you how to do it better.” Most people don’t want to hear that. “Listen, I can make a better pie than you can; let me give you my recipe.” No, you’ll get along a lot better if you start out asking advice. “Your pie crust always seems so light and flaky; how do you do it?” “We always seem to be having these arguments; how do you keep everyone on board?” Start from weakness, not strength; from need, not superiority. It works in families, factories, congregations, government . . . every level of human relationships. How can you help me, not how can I help you. Suppose the President were to call Nancy Pelosi and say, “Look, we’ve got to get a solution to . . . . well, you name it: the border, the budget, the virus, whatever) and I’d really like your thoughts.” He’d have to persuade her it wasn’t a hoax . . . but just suppose.

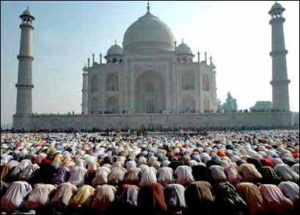

Or churches: maybe if we spent more time trying to learn from the evangelical churches they’d be more open to learning from us. Its worth trying. Jesus’ example is always worth following. Moslems pray five times a day and fast all day for thirty days in a row. Is there something there to open  a conversation that might be more productive than urging them to accept the Trinity? Well, that’s point one. Think about it in terms of any relationship that isn’t working for you; any division from someone else that concerns you.

a conversation that might be more productive than urging them to accept the Trinity? Well, that’s point one. Think about it in terms of any relationship that isn’t working for you; any division from someone else that concerns you.

Then notice this: once the conversation is going, Jesus moves it on to deeper things. Not just water from the well, but the life-giving water that God alone can give. We all need the same things. It doesn’t matter whether you are Episcopalian or Baptist, whether you are Christian or Moslem, all human beings need a deeper relationship with God. And, yes, Jesus alone can provide that and he makes that perfectly clear, but not on a “You want it; I’ve got it” basis. No, what he says is, “There is this water of life that you need and it’s available if you only ask.” Always he respects her freedom. It’s up to her to ask and he will not force it on her. Most people don’t want to be threatened or coerced or have their arms twisted. There are churches that come on with an attitude: “Join us or go to hell.” It works for some people, but not most. Most of us, I think, given a choice, would rather stay where we are than accept a gift under compulsion. Maybe your neighbor has the latest thing in computers and you’re still using a pencil or a beat-up old typewriter and they come along saying “How come you’re so stupid; let me give you a computer and show you how to use it so you can be almost as smart as I am.” No, it doesn’t work. “Let’s go together, grow together” works better. Jesus offers but never insists.

And a third thing: don’t get bogged down on the outward and visible. The Samaritan woman wants to talk about things she understands like, “Is it better to worship in Jerusalem or Samaria?” “This mountain or yours?” And Jesus just won’t go there. “God is spirit, and those who worship God must worship in spirit and truth.” If you’re having ecumenical conversations with Roman Catholics what matters is not the number of statues you have but the love of God. If you’re talking to evangelicals the issue is not that we use vestments and they don’t. The issue is the love of God. The issue is the presence of God’s Holy Spirit in your heart and mine. People come into an Episcopal Church and see some people crossing themselves and some people genuflecting and that’s what gets their attention. Do Episcopalians have to do all that? No. They don’t. Many find it helpful. Some don’t. At the Last  Judgment, I don’t think this will even come up for discussion. Does it matter whether you worship God on Mt Gerizim or in Jerusalem? No, it matters whether you worship. It’s better to be a good Roman Catholic than a bad Episcopalian; a good Moslem, than a bad Christian. “The hour is coming, and is now here, when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for the Father seeks such as these to worship God.”

Judgment, I don’t think this will even come up for discussion. Does it matter whether you worship God on Mt Gerizim or in Jerusalem? No, it matters whether you worship. It’s better to be a good Roman Catholic than a bad Episcopalian; a good Moslem, than a bad Christian. “The hour is coming, and is now here, when the true worshipers will worship the Father in spirit and truth, for the Father seeks such as these to worship God.”

I need the help of outward and visible things: a church building, a sense of beauty, candles and crosses and vestments. But Jesus was born in a stable and I can worship God in a stable. I’ve prayed in pretty simple surroundings and it’s doable. Yet if I take the time to beautify my own home and leave God’s house bare, I’m not sure the Spirit is present. I’m not sure I can claim to be bringing my best, really offering my life to God if I leave the floor unswept and last week’s programs lying on the floor and a vase of drooping flowers on the altar and conduct the service in an old flannel shirt and blue jeans. But it’s not the vestments that matter or the location of the church. Those may be evidence of the Spirit but they are not the Spirit, and God is looking for the Spirit, for lives that truly honor God.

Week after week we hear about Jesus healing or Jesus teaching or Jesus doing miraculous things. But I suspect what made the real difference was the way he talked with people: last week with Nicodemus, this week with an un-named Samaritan woman, next week with a blind man: listening, showing respect, allowing them their freedom, pointing them toward the things that matter. And like most things we hear in church, it shows us some things we ought to pay attention to and remember and act on.

other. The prophets said, “It doesn’t matter where you are or what the agenda is; there is one God, no other. You can serve God, but God can’t be bribed to serve you.” But the practical people said, “Look, the Canaanites have the experience and the smart thing is to hedge your bets, not put all your eggs in one basket, always backup your computer, don’t take chances.”

other. The prophets said, “It doesn’t matter where you are or what the agenda is; there is one God, no other. You can serve God, but God can’t be bribed to serve you.” But the practical people said, “Look, the Canaanites have the experience and the smart thing is to hedge your bets, not put all your eggs in one basket, always backup your computer, don’t take chances.” deprivation,” I think might be the modern phrase, removal of distractions. And who needs some such practice more than 21st century Americans whose lives are so full and whose souls are so empty? Lent is a time to clean house, to be rid of idols and images and preconceived notions and start afresh.

deprivation,” I think might be the modern phrase, removal of distractions. And who needs some such practice more than 21st century Americans whose lives are so full and whose souls are so empty? Lent is a time to clean house, to be rid of idols and images and preconceived notions and start afresh. that this is not truly desert but wilderness. There is a difference. Desert, true desert, he said, is where nothing can grow. Wilderness is where growth can take place if only it has water. When the spring rains come it bursts into bloom. When the aqueduct springs a leak, the barren land turns green.

that this is not truly desert but wilderness. There is a difference. Desert, true desert, he said, is where nothing can grow. Wilderness is where growth can take place if only it has water. When the spring rains come it bursts into bloom. When the aqueduct springs a leak, the barren land turns green.

problem. Through the years, religious books have often been at the top of the “how to” list. I remember one called “the power of positive thinking,” and more recently one called “the Be Happy attitudes.” Currently there’s one co-authored by the Dalai Lama and Bishop Tutu called “The Book of Joy.” Joy, happiness, God on your side. It’s an age-old search. And all too many of us, even if we’ve outgrown it ourselves, try to push it on our children. I’ve heard it 100 times: “I want little Suzy to be in the Sunday school because I think it’s good for children to learn about God and how to behave and get some ethics.”

problem. Through the years, religious books have often been at the top of the “how to” list. I remember one called “the power of positive thinking,” and more recently one called “the Be Happy attitudes.” Currently there’s one co-authored by the Dalai Lama and Bishop Tutu called “The Book of Joy.” Joy, happiness, God on your side. It’s an age-old search. And all too many of us, even if we’ve outgrown it ourselves, try to push it on our children. I’ve heard it 100 times: “I want little Suzy to be in the Sunday school because I think it’s good for children to learn about God and how to behave and get some ethics.” we need. His life transforming ours. Why do we do what we do? Because Christ in us so shapes our hearts and minds that we love what he is and do what he does and become who he is. When that happens “should” becomes a meaningless word.

we need. His life transforming ours. Why do we do what we do? Because Christ in us so shapes our hearts and minds that we love what he is and do what he does and become who he is. When that happens “should” becomes a meaningless word. Christopher L. Webber

Christopher L. Webber