A sermon preached by Christopher L. Webber at St. Paul’s Church Bantam, Connecticut 0n Advent Sunday, November 28, 2010

A sermon preached by Christopher L. Webber at St. Paul’s Church Bantam, Connecticut 0n Advent Sunday, November 28, 2010

My text this morning will be toward the end of the sermon. This is Advent Sunday, the beginning of a new year, and I want to begin at the beginning, with the story in the book of Genesis of the creation of the world. “In the beginning, God created the heavens and the earth” and, having created everything else, God created human beings. “God said, “let us make human beings in our image, in our likeness, and let them have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the earth . . . so God created human beings in the image of God, in the image of God they were created, male and female they were created.”

God created us in the image of God. Have you ever stopped to think what that means? We think modern scientists has given us a high view of human nature. We think that 21st-century human beings have a greater image than ever before of human greatness, human abilities, human capacities. We think that because we learned to travel in space, that we can walk on the surface of the moon, that we have discovered how great human beings are. Look again at the first chapter of Genesis and see what the Bible has to say about us: it says we were made in the image of God. No one before or since has ever equaled that statement in what it claims for us.

But let me read you a quotation from someone else who makes great claims for human ability:

“Who, then, can fully express the preeminence of so singular a creature? Man contemplates the mighty deep, contemplates the range of the heavens, notes that motion, position, and size of stars, and reaps a harvest both from land and sea . . . he learns all kinds of knowledge, and skill, and arts, and pursues scientific inquiry. He rules everything, subdues everything, enjoys everything. He gives orders to creation.”

Now, if you noticed that that statement wasn’t in inclusive language, you might suspect it wasn’t written recently. But I think you might not guess it was written by a Christian bishop (Nemesius of Emessa) 1500 years ago. Our modern knowledge of life only adds a little bit, and takes nothing away from, the knowledge that Christians and Jews have had for thousands of years. To know how many thousands of cells, constructed for how many different purposes, nourished by how intricate a system of blood vessels, go to make up even so small a thing as the human eye – — what is that compared to the claim that we were made in the image of God? Take all the wonders of modern discovery together, they fall far short of that discovery: human beings, in their essential nature, are like God..

You have to realize how marvelously high a view the Bible takes of human life to see why it’s also speaks out so insistently against human failures. Only when you see where we started and how high up we began, is it possible to be really concerned with where we are now and how far we have fallen.

There are three parts to the story. Part one, the beginning, reminds us of what we were made to be. Part two tells us what has happened since and where we are now.

Unless you were born blind, you know there is more to human makeup than simply a resemblance to God. In fact, you might well have had your eyes open most of the time, and not yet noticed that resemblance in others, and you might not even have seen it in yourself. That doesn’t mean it isn’t there. It does mean that it’s hidden and concealed and overlaid with something else. And there is a story in the book of Genesis that tells us in its own way how that came to be. Told in another way the story would go like this–and it’s not just a story about the first man and woman, it’s a story about you and me – men and women were not and are not satisfied to be like God, they want, no matter how they express it, to be God. We want to use the mind and strength and creative power God has given us to serve not God but ourselves.

Now, if you have ever worked with machinery, whether in the kitchen or factory or home workshop, you know that if you use a tool for the wrong purpose, it becomes useless for any purpose. If you haven’t got a screwdriver and try to make do with a chisel, you will find out soon enough that that kind of chiseling doesn’t work. It doesn’t make a good screwdriver and it no longer works very well as a chisel. Human nature is like that. When we put ourselves first and work for ourselves, we put ourselves in the place of God and in the process we can ruin ourselves and others.

There is a 19th century novel you might have read by Oscar Wilde called, The Picture of Dorian Gray. It shows more clearly than any example I know, how this self-destruction takes place. It’s the story of a young and handsome man with a great, life-sized painting of himself that he keeps on an upper floor of his house. The story describes the career of this man as he goes through life and yields to its temptations, indulging himself, pampering himself, using others for his advantage, hurting and injuring others to get his own way. The remarkable part of the story is that in all that he does, he never changes to outward appearance. Though the book shows clearly the increasing evil of his life, he always appears the same to others. He doesn’t even seem to grow any older. But the picture does change. From time to time, Dorian Gray goes to look at this handsome picture of himself and he notices – – not much at first, just a hint here and there–but the picture itself is changing and it reflects the person he is becoming. At first, there are simply a few harder lines around the mouth, but then wrinkles and folds appear and the eyes grow hard until the picture is that of an old and very evil man.

The story is one that makes you shiver to read it because we know as we read it that in some ways we are not so very different from Dorian Gray..And this is especially true for the Christian who knows he or she was created in the image of God and that each thoughtless act, each selfish thought, each unkind word, leaves its mark on the image and reduces that likeness to God. Maybe it doesn’t show too much at first on the surface, not too much anyway, because it is really a spiritual thing, but slowly and surely that process is taking place and the character God gave us is being damaged and lost. Just as the picture of Dorian Gray was made ugly by the life of its owner, so the likeness of God in us is perverted, deformed, defaced, by the lives we often lead.

What would you say.if you owned an expensive and beautiful painting and came home one day to find that a child had scribbled on it in crayon? Would you stand by while someone slashed a painting of Jesus and threw mud at it? But sin does that to us. It takes that nature that God has given us, that likeness to God that enables us to call God our father, and smears and slashes and hides it till no one would know what we once were. We ourselves destroy the image of God in ourselves as surely as if we threw mud.

The horror of sin is not simply that it violates God’s will and commandments; those are simply a description of the purpose for which we were made. The horror of sin is that in denying that purpose, in trying to do and to be something for which we were never intended, something we have no ability to be, we destroy that good thing that we are by nature, and the good life for which we were intended is damaged and twisted for us and for others.

So now we have two parts of the story, and fortunately there is still part three.

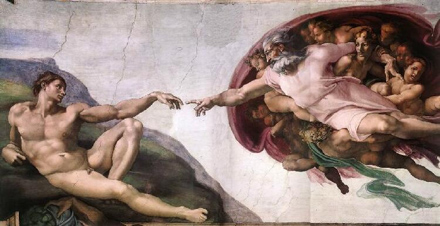

The contrast between what God intended us to be and what we have become leaves us in need of some way out of the dilemma. The story of Dorian Gray might suggest part at least of the answer. The problem we have is that we no longer have any way of seeing what we used to look like. Once human sin began to cloud over the original nature of humanity there was no way left to see what we had once been like. Dorian Gray at least had a picture. He could go and see what he was doing to himself. He could compare the changing picture with his own changed outward appearance and see just how far he had come. Perhaps if we had a picture that didn’t change – –that showed us the original likeness of God in human nature – — we could at least see the damage and try to do something about it.

Well, the good news is, we have such a picture. Jesus of Nazareth shows us in his life the likeness of God in human nature. St. Paul uses that phrase to describe him time and again: “Christ, who is the image of God. . .” Why, after all, does the second commandment prohibit making any carved image to worship? It was because God could only be revealed in a perfect human life. The only likeness of God that we are given to look at is Jesus our Lord. Jesus reveals to us the likeness of God in which we were created, not simply to show us by comparison how far we have fallen from it, but also to make it possible for us to regain that likeness in ourselves. The Gospel, the good news of Christ and the apostles and Church and the Bible is this: that God sent his son into the world to put on human flesh so that we might put on ourselves the likeness of God that we had lost.

So now we come to our text which we heard in the second reading: “Put on the Lord Jesus Christ.” What we are talking about is not simply the imitation or hero worship or copying of some other person that we admire. That’s all very well if it builds similar good qualities in us, but it can cramp and hinder us just as well. It’s all very well to copy someone else’s golf swing or the latest fashion in cloths, but who do we want to be: Tiger Wood or Sarah Palin or ourselves? To put on Christ is to put on our true selves, to follow him is to become who we really are. We had forgotten, we had lost ourselves, we had become accustomed to the sin and failure in which we live, but Christ has come and is coming and we can see now who God wants us to be.

The Advent season puts a special emphasis on what we should be doing all our lives: preparing to receive our King. And Christmas puts a special emphasis on what happens as often as we come to Communion: Jesus comes to us. But when he comes he needs to find us ready and this is a time for preparation, time as the collect today tells us “to cast away the works of darkness and put on the armor of light,” time to put away the old Adam and the damaged image of God, time to put on the new nature, the restored image in Jesus, a time to put on the Lord Jesus Christ and let him shape our lives to become at last what they were always meant to be and can be and will be when we receive him, receive him, in our hearts.