In Ingmar Bergman’s movie, the Seventh Seal, a knight is confronted by Death but argues that he needs more time to gain assurance about his faith. He bargains with Death, who agrees to play a chess game to determine the knight’s fate. So the knight continues on his way and, after a number of adventures, falls in with a little family and agrees to escort them through a dark forest.

In the middle of the night, Death comes for the whole group but when he sits back down to the chess game the knight tips over the board. In the confusion, the little family escapes but, in the final scene, the knight is seen silhouetted against the sky, being led off in the Dance of Death by Death with his scythe. The knight never gains the proof he wants for his faith, but he acts anyway to save the small family at the cost of his life. Does it matter, the movie asks us, whether you have faith if you act as if you did?

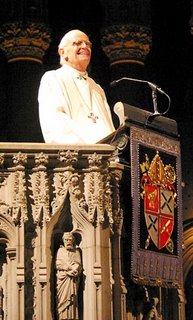

The current issue of the New Yorker features a narrative about Bishop Paul Moore of New York written by his daughter. She talks about the way she looked at her father growing up as he preached or presided at the Eucharist. Reference is made to his work in an inner city parish, his anti-war activity, and his advocacy for homosexuals. She talks about his separation from his wife and a problematic second marriage. Eventually she tells us how she learned that her father also apparently had a sexual relationship with one or more men.

The story is well written, though episodic, but what does it tell us that we need to know? That human beings act from a variety of motives? Don’t we know that? What good does it do to tell us very small pieces of a very big story? Does it enhance our understanding of anyone or anything?

Paul Moore was a big man and a powerful presence in the church and the larger society. He forced people to think about issues they might have liked to avoid. I sometimes disagreed with him strongly and said so publicly, but I respected him and our disagreement never became personal.

What bothers me about this New Yorker article is that it seems to diminish a remarkable man to no purpose. So some aspects of his life were a mess. So he never got his sexual life neatly organized. So he and his daughter didn’t fully understand each other and were estranged for awhile. So how many of us have all our ducks in a row? And how many of us have dared stand up against the government or against social norms and expectations – and made a difference? Perhaps the fact that everything was not easy for the bishop makes his accomplishments that much more notable.

Like the knight and the bishop, we all struggle with some aspects of our life and faith. That’s not worth writing about – except, perhaps, to remind us that we aren’t the only ones who don’t score a ten every day, but that we might still make a difference for others that would make our lives worthwhile.

************

Having written the above, I received the following letter sent to the Diocese of New York (forwarded to me). I think we are saying the same thing but weighted differently. Bishop Sisk needed to write his letter. I’m glad he did. I also needed to write my blog.

***************

February 29, 2008

To the clergy and people of the Diocese of New York

My Dear Brothers and Sisters in Christ,

It is with sadness that I write to you.

The March 3, 2008 issue of The New Yorker contains an article by Honor Moore which is drawn from her forthcoming book A Bishop’s Daughter (prepublication copies of which are in circulation). While the book is, in the main, autobiographical, Ms Moore goes into considerable detail about the private life of her father, Paul Moore, Jr., the 13th Bishop of New York.

Her description of him comes as a shock to many of us. The man that so many of us knew and admired was a man of enormous personal courage, a passionate, articulate, and tireless champion of the poor, the disenfranchised and the most desperately helpless in society. He was all that, but as Ms Moore tells us there was another side to him, a man who led a secret double life. While on the one hand he inspired people to work for, and hope for, a community that could stand against the powers of oppression and exploitation, on the other he was himself an exploiter of the vulnerable.

Ms Moore’s article brings to light what appears to be her father’s decades long violation of his wedding vows. This was an offense of the most serious nature. Any person who has extra-marital relations commits an offense. This is true whichever party is married: whether clergy or lay, same-sex or heterosexual. Whatever the circumstances, it is family relationships which are broken. And, indeed a point of Ms Moore’s article would seem to be just that: the relationships between Bishop Moore and Ms Moore and her mother indeed were evidently severely damaged. The preservation of those relationships is an important aspect of the Christian life and of course of the life of its ordained ministry. Actions such as those which Ms Moore reports are wrong and could quite conceivably result in the most severe penalties that the church can apply to an ordained person.

But there is more. It appears as well that Bishop Moore violated his ordination vows in another respect. The long term extra-marital relationship that his daughter describes was begun, according to her account, with a young man who had come to the Bishop for counseling. That inappropriate relationship is a fundamental violation of an ordained person’s vow to minister to the needs of those entrusted to his or her care; never is this more so than when working with the vulnerable who have come seeking pastoral care. Sadly the violation of trust that Ms Moore reports is consistent with behavior recorded in complaints about Bishop Moore’s exploitative behavior received by the office of the Bishop of New York. As Canon Law required, the concerns of those complainants (who wished their identities held in confidence) were duly conveyed to the then Presiding Bishop Edmond Browning for disposition.

Though A Bishop’s Daughter reveals Paul Moore to have been a vastly more complex man than many of us who admired and respected him ever knew, and though there can be no excuse for the enormity of the betrayal of personal trust that he perpetrated in his private life, yet similarly there can be no diminution of the greatness, the nobility even, of the purposes and goals of his public life. We are left seeing a deeply flawed man in desperate need of God’s merciful grace. As are we all.

Faithfully yours,

+ Mark Sisk, Bishop of New York

The New Yorker podcast for the March 3 edition is an interview with Honor Moore, who speaks of her father with great love, admiration, and sympathy. She touches on this issue–why write this?–and comes to the conclusion that in the writing she got to know and sympathize with her father more than she had in life. That doesn’t, of course, answer the question–why publish?–but it may hint at it as well. I haven’t seen the issue yet (my New Yorkers get here late) so I can’t speak to the tone of the piece, but she was quite open and forthright in the interview.