Being Like God

A sermon preached at All Saints Church, San Francisco, by Christopher L. Webber on April 15, 2018.

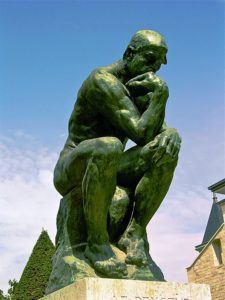

Many years ago, I had an assistant who was just out of seminary and one Sunday it was his turn to preach – maybe the first time he had done it. The epistle reading that morning was I Corinthians 13, the great passage about love: “Faith, hope, and love remain, but the greatest of these is love.” So the time for the sermon came and he went to the pulpit and read it again and then he said, “That’s just so beautiful, I don’t think there’s much I can add to it, so let’s just take some time to think about it” And then he sat down and out his chin on his fist like that famous statue of “The Thinker” by Rodin, and we all waited to see what would happen next and I have to admit that I didn’t think about I Corinthians 13 at all because I was trying to think of a way to move the service ahead.

I remembered that this last week when I started to think about this sermon and the readings we have just heard and was I drawn to the reading from the First Epistle of John and wondered what more could be said and whether that young assistant’s approach might not have something to be said for it. Listen again to John:

See what love the Father has given us, that we should be called children of God; and that is what we are. Beloved, we are God’s children now; what we will be has not yet been revealed. What we do know is this: when he is revealed, we will be like him, for we will see him as he is. I John 3:2

What more is there to say? John himself runs out of words: “What we shall be has not yet been revealed. What we do know is this: when he is revealed, we will be like him, for we will see him as he is.”

I’ve spent a lot of time in recent sermons talking about the difference it makes to be a Christian but I’ve been talking about it in terms of the impact we ought to make on the world around us. Today, if we pay attention to the epistle, we’re asked to think about the difference it makes in us and, really, we probably ought to think about that first because how can we make a difference in the world unless we ourselves are different?

But here’s the problem: the difference comes in two ways and one of them is beyond words. Last week John was plain and simple: “If we say that we have no sin, we deceive ourselves.” But, you know, dealing with sin is the easy part. we confess and we are forgiven. Well, that’s easier to say than to do, but at least you can say it and sometimes, on our good days, we can do it. But John is pointing us beyond that. He’s saying sin and forgiveness are just a first step toward a future beyond words and beyond imagination. “Beloved, we are God’s children now; what we will be has not yet been revealed.”

There are two steps there: first, “we are God’s children now.” We could sit for awhile and contemplate that. Do you take it for granted? You shouldn’t. I think we sometimes write it off as something that’s a “given,” as if it comes with being born: “all human beings are children of God; we’re all God’s children.” You hear people say that, but I don’t think so. God is the Creator and all human beings, like all cats and dolphins and sheep and red-tailed hawks are God’s creation. But not God’s children, not part of God’s family. Potentially, yes, but to become a child of God requires baptism; it’s what baptism is all about.

But not God’s children, not part of God’s family. Potentially, yes, but to become a child of God requires baptism; it’s what baptism is all about.

When we baptize a child the whole congregation joins in saying, “We receive you into the household of God.” In other words, “Welcome to the family; the family of God’s children.” We are children of God, the Bible tells us, not by nature, but by adoption and grace. St Paul talks about it in the Epistle to the Galatians:

God sent his Son, born of a woman, born under the law, in order to redeem those who were under the law, so that we might receive adoption as children. And because you are children, God has sent the Spirit of his Son into our hearts, crying, “Abba! Father!” So you are no longer a slave but a child, and if a child then also an heir, through God. (4:4-7)

So that’s an amazing first step toward an even more amazing future: God, the Creator of the universe, makes human beings of dust and then provides a way for us, these creatures of dust, to become God’s own children. And what John is meditating on is that this has consequences, it has to be only a first step because we earth creatures, on the surface at least, have nothing in common with the eternal God.

We say on Ash Wednesday, “You are dust and to dust you shall return.” But if so, why bother? Potentially, at least, there seems to be something more and it’s hinted at already in the first chapter of Genesis. It says, “God created humankind in the image of God.” We may be only dust but there is something in us from the very beginning capable of reflecting God. And what would that be? How do we, in any way, resemble God?

Well, of course, what often happens is that we draw pictures of a God who resembles us. We make God in our image. Even the great artists – da Vinci, Michelangelo – picture God as an old man on a cloud: God, in the paintings, does look a lot like us. And what else can they do? If God doesn’t look like us, what does God look like? But the Bible actually tells us a lot about what God is like and some of it can be seen in human life: there’s justice, for example. God is just and we are somewhat just, we aspire to be just. Maybe we know someone or know of someone who seems to be absolutely fair and just in their dealings with other people: a teacher who gives equal attention to every child, a businessman or woman who treats every employee and customer fairly, a politician who is never influenced by money or special interests. God is like that – only more so – and God is merciful and forgiving. Above all, God is love. And these are qualities we see in human beings and admire and we know that we all have the potential to embody these qualities more fully than we do. We could be more like that. And maybe we can dimly imagine someone who really is like that completely, perfectly. Out there, somewhere, we might imagine is one who embodies these qualities perfectly and what we see is just a pale reflection of our potential.

So in a sense God is like us, but infinitely, unimaginably more. God’s justice and love and so on, of course, are so far beyond ours that the resemblance is only slight but we do instinctively know when we see mercy and forgiveness and self-forgetting love in a human being that that’s what we ought to be. We know instinctively that God is like that and we ought to be, ought to be and can be.

We have that potential. And those qualities, when we see them, give us a glimpse of God. And of course that’s why the followers of Jesus Christ very soon began to say that in seeing and knowing him they had also come to know God. “God was in Christ,” said St Paul, “reconciling the world to himself.” God was in Christ showing us what God is like and drawing us back to that lost likeness, that image in which God first created us, and that we so quickly lost at the very beginning.

John says, “We are God’s children now; what we will be has not yet been revealed. What we do know is this: when he is revealed, we will be like him, for we will see him as he is.”  So baptism makes us the children of God by adoption and grace and starts us on the road home. But even knowing Jesus, we don’t really know what we will be. We have only seen Jesus in human form. What will he be like in glory? We can hardly imagine. And will we be like that? Yes, that’s what John tells us. Yes, we can hardly imagine, but we will be like that.

So baptism makes us the children of God by adoption and grace and starts us on the road home. But even knowing Jesus, we don’t really know what we will be. We have only seen Jesus in human form. What will he be like in glory? We can hardly imagine. And will we be like that? Yes, that’s what John tells us. Yes, we can hardly imagine, but we will be like that.

I’ve been talking the last few weeks about the failures of American Christianity and maybe the greatest of all is that it sets its sights so low. It tells us to be happy or be good or repent but John points beyond all that to something unimaginable. He tells us we were made for glory, and that glory dazzles human eyes. We would need new eyes to see it, new bodies to live it. But that’s what John wants us to understand: we were made for a glory so far beyond our understanding that no revelation can show us and no words contain it. It’s not a question of keeping the commandments, not even a question of loving God and loving our neighbor. That’s all well and good and we need to be working at it, but it’s a question of growing into God and I think that’s why there’s eternity. It may well take an eternity or two even to begin to be who God made us to be.

John Donne, as usual, said it best almost 400 years ago:

“Can you hope to pour the whole sea into a thimble or take the whole world into your hand? And yet, that is easier than to comprehend the joy and glory of heaven in this life. For this eternity, this everlastingness, is  incomprehensible in this life.”

incomprehensible in this life.”

Incomprehensible, yes, but now, right now, we can make a beginning. We can remember our baptisms, the baptism that made us God’s children. We can come here to be fed at God’s table; how could we grow up without food, after all, and that food is Christ himself because we are called to grow into Christ, to be members of his body. And then we can pray and ask God’s help daily to draw us closer to that destiny for which we were made and which we will never fully understand until we are there in the presence of God and able to be at last all we are meant to be and what we can begin to be now.

Christopher L. Webber

Christopher L. Webber

Good stuff Chris. Thanks. I plagarized again. And added to the John Donne bit by quoting the other metaphysical great, George Herbert’s King of glory…. een eternity’s too short to extol thee. All best

Lesley

Dear Mr. Webber,

I am glad to have an autographed copy of your book about James Pennington, but I noticed an oddity in it: on the title page (but not on the dust jacket), the word is spelled “Abolishonists”.

I figure there must be some story behind it (if only of author’s angst on seeing it) and am curious to know about it.

Would you enlighten me?

Thank you,

David Nolan

St. Augustine, FL

(not far from Pennington’s final resting place…)