The Rock Was Christ

A sermon preached by Christopher L. Webber at St Paul’s Church Bantam, Connecticut, on March 3, 2013.

When our ancestors came out of Egypt, they wandered for years in the desert and often lacked food and water. Again and again, they complained to Moses and Moses complained to God, and finally God told Moses to strike a rock with his rod, and Moses did, and water gushed out to satisfy the people’s thirst. Then, the tradition is that that rock followed them as a constant source of water whenever the people got dry.

Now that tradition is not in the Bible except second hand in this morning’s epistle which calls it a “supernatural rock” and goes even further to say that the supernatural rock was Christ. Well, any rock that follows you around is supernatural, for sure. That’s not what rocks normally do, and living in Connecticut we’ve seen plenty of rocks and know how rocks behave. A natural rock just lies there. They may seem to move up out of the ground, but they say it’s the frost that does that. Frost moves them up and frost knocks them down out of walls and generally rearranges them but otherwise a natural rock stays pretty much where nature put it.

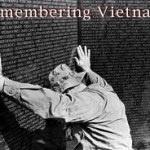

But suppose you take one of those natural rocks and put it in the hands of a great artist and suppose that artist carves it into the likeness of Abraham Lincoln sitting in a chair looking down at the tourists, or Rosa Parks sitting in a chair looking out at the crowds. Or suppose you take a supply of those rocks and form a wall and carve into that wall the names of soldiers killed in Viet Nam . Or suppose you take a piece of stone and place it above the grave of someone you love and carve their name into it. Is that still just a natural rock? Can we treat it the way we treat any other rock, or have we made it something more?

But suppose you take one of those natural rocks and put it in the hands of a great artist and suppose that artist carves it into the likeness of Abraham Lincoln sitting in a chair looking down at the tourists, or Rosa Parks sitting in a chair looking out at the crowds. Or suppose you take a supply of those rocks and form a wall and carve into that wall the names of soldiers killed in Viet Nam . Or suppose you take a piece of stone and place it above the grave of someone you love and carve their name into it. Is that still just a natural rock? Can we treat it the way we treat any other rock, or have we made it something more?

There’s an ancient distinction between the eye of the flesh, and the eye of the mind, and the eye of the spirit. The eye of the flesh sees a rock: rough, gray New England granite or limestone or sandstone – but rock, a natural rock, a part of the landscape, an obstacle to the spring plowing, something to kick out of the way. Or maybe the natural eye doesn’t even see it because you’ve seen them all before and you don’t even bother to look. But the eye of the mind can see something more: a collection of atoms of a particular type, the product of volcanic action or sedimentation or some other natural process that shaped it and determines its nature. If you’re a geologist or scientist, you’ll find that interesting and something to examine and study. But the eye of the spirit sees not the natural stone carved in some way but Abraham Lincoln or a man you grew up with or your grandmother and is deeply moved by seeing their name or figure carved into it and would be outraged if someone should come along and kick that stone as you might normally do to the same sort of rock any day in a field.

All rocks are not the same rock, and some have eyes to see the difference. If you were told that this rock I hold in my hand is a piece of Plymouth Rock or a piece of the rock that was rolled in front of the tomb of Jesus you might feel it had a holiness that made it almost too special even to touch.

What all this leads up to is a question: Can we draw any clear line that separates different kinds of rock or that distinguishes a natural rock from something more, so that we might even call it “super-natural?” I’m really not sure that the terms natural and supernatural are very useful. “‘Natural” implies that we can measure it, touch, taste, and feel it. Philosophers like to talk about physical and metaphysical, but how useful is that? Is love natural or supernatural? Where do you draw the line between natural sexual reproduction and a natural effort to propagate the species and even sacrifice for that purpose and the altruistic and self-giving love that moves the sun and the seven stars? Can you really draw a line between different aspects of the world God made and say this is natural and this is not? Can you ever say God is here and not there? Or is it simply all one; is the universe simply – as the name implies – a single entity in which we see some things more clearly and easily than others but in which everything except God is in fact created and very natural?

I’m getting into some pretty complicated stuff here and I’ll have more to say about it next week because I want to say some things about the Eucharist, the Communion, The Mass, the Liturgy, because it’s our basic act of worship, our family meal, the center of Christian life and we come at it with all sorts of conceptions and misconceptions. Years and years ago, I got an offertory procession introduced in the congregation I was serving – bringing bread and wine to the altar from the congregation – and one member quit because it was high church and another member quit because it was low church. That’s why it’s important, I think, to be as clear as we can about this whole idea, of natural and supernatural because the bread and wine we receive at the altar are sometimes thought of as supernatural and I think that misses the point. They are holy, yes, and special beyond doubt but Christians have spent far too much time and energy debating and condemning each other for holding the wrong ideas about the exact meaning of this service and this food. And what happens when we debate and argue about it is that some people wind up denying Jesus’ presence here at all because they feel a need to draw a line between nature and super-nature and define how God crosses that line to be with us and whether and how God can or can’t do it. But what if there is no line? What if, like the granite that becomes holy when we use it for holy purposes, the bread and the wine also become holy because we put them on the altar and re-enact the Last Supper and remember Jesus’ promise: This is my body; this is my blood.

In the middle ages, Christians were not satisfied with that simple statement. They wanted answers for everything so they tried to define how, and in what way, the bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ. And I’m not sure you can do that without crossing the line into magic. They asked how it happened and they got involved in definitions of transubstantiation and consubstantiation and trans-signification but all they were trying to say was “Jesus is really here: in this bread and wine Jesus is really present.” But once they got a definition of what happened that satisfied them they went on to ask when it happened: at what moment does the bread and wine become the body and blood of Christ. They answered: When the priest says, “Hoc est corpus meum:” “This is my body.” And they said, `’Well, OK, but exactly when?”” And they answered: “Between the two syllables of the word corpus in the phrase ‘”Hoc est corpus meum.” And out of that debate we got the phrase “Hocus pocus.” And that’s a pretty good commentary on the value of that discussion.

Let’s try to be practical. We know instinctively what makes something holy. You take some material thing – let’s say some rocks or bread and you shape those rocks or that bread for your purpose and you call together an assembly of people and you bring on someone appropriate and  you have a ceremony. Maybe you carve in stone the names of Vietnam Veterans and call in the President and you have a ceremony and then surviving veterans or family and friends of those who died will go there and be deeply moved and feel closer there to those who died than anywhere else. Now, if we can do that, can evoke that sense of presence in ordinary stone, think what God could do not just to evoke but to make real Christ’s presence in bread and wine.

you have a ceremony. Maybe you carve in stone the names of Vietnam Veterans and call in the President and you have a ceremony and then surviving veterans or family and friends of those who died will go there and be deeply moved and feel closer there to those who died than anywhere else. Now, if we can do that, can evoke that sense of presence in ordinary stone, think what God could do not just to evoke but to make real Christ’s presence in bread and wine.

But suppose the people remembered in our carved stone had died not on any battlefield but simply of old age. Would the memorial have the same power? I doubt it. Meaning and purpose and ceremony are all very well, but there’s still something more and we try to get at it when we use that strange word: “sacrifice.” The word “sacrifice” comes from two Latin words that mean simply: “make holy.” I think Abraham Lincoln had it right when he went to the battlefield at Gettsyburg: and said, “In a larger sense, we cannot dedicate – we cannot consecrate – we cannot hallow this ground. The brave men, living and dead, who struggled here, have consecrated it far above our poor power to add or detract.” To consecrate a battlefield – requires a ceremony and an appropriate person but also sacrifice. And to consecrate the bread and wine requires not only a ceremony and appropriate person but also sacrifice. It takes a ceremony and a priest and a congregation. Archbishop Crammer got that right when he required in the first English Prayer Book that there be two or three at least to receive communion or there could be no service because Christian people share in priesthood with the priest. You have a priesthood without which the Eucharist can’t happen. This is not a magic act in which a priest takes bread and does a hocus pocus and we then get a sacramental fill-up. That kind of thinking is sacrilegious.

I think we know better. I think we know instinctively that the presence of the holy God is focused in the eucharist in this bread and wine that we call holy but that holiness comes about because of Jesus’ sacrifice and our faith and the joyful celebration that occurs when Christians gather and remember Jesus and know him to be present with us and offer ourselves in God’s service. It’s like what happened that day at Gettysburg and like what happened at the Vietnam wall but far beyond and above all our human memorials because here it is the living God who takes this bread and uses it not simply to be remembered – but to be present, to be here and to feed us and nourish us and strengthen us, and give us life: life now and life forever.

Christopher L. Webber

Christopher L. Webber