Playing to Win

A sermon preached at St. Paul’s Church, Bantam, Connecticut, on February 12, 2012, by Christopher L. Webber.

Did you know that baseball spring training began yesterday in Florida? This week baseball players will be gathering in Florida and Arizona to spend six weeks practicing and preparing and getting in shape for a six month season. And a good part of that six months will also be practice: batting practice, fielding practice, and constant drill and discipline in order to do it right.

I had a friend once who had been a champion badminton player and I would see him go into a gym and spend an hour or more practicing just one shot until he had it right. When I knew him, he was no longer playing in competition, but he knew what it takes to do something well and he wanted to do it as well as he could.

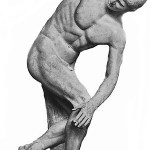

St. Paul is talking about exactly that sort of discipline in this morning’s epistle and he uses the language of sports and competition: “those who run in a race all run, but one receives the prize; so I run, not like someone fanning the air, but I discipline my body and bring it into submission.” That’s taking faith seriously, as something worth working on, not just dropping in occasionally on Sunday morning for a spiritual pick-up and emotional boost but working to put the whole of life in the service of a Lord who has given us all of our life and can enrich and direct that life if we offer it deliberately and carefully and thoughtfully.

Discipline was something Paul knew about the same way we do: by watching athletes train. He was writing to the church in Corinth and it’s only about fifty miles from Corinth to Olympus where the Olympic games were still being held. Maybe Paul had been there; but whether he had or not, he certainly knew about Greek athletics. Athletics was really part of Greek religion; the Olympics involved not only the contests but processions and sacrifices and offerings to the gods.

miles from Corinth to Olympus where the Olympic games were still being held. Maybe Paul had been there; but whether he had or not, he certainly knew about Greek athletics. Athletics was really part of Greek religion; the Olympics involved not only the contests but processions and sacrifices and offerings to the gods.

\

Some people think sports is becoming a religion again and maybe in a way it is, but a one-sided religion, lacking the spiritual discipline that Greek sports included and that oriental sports like judo still include. Spirit and body need to work together; an athlete needs mental and spiritual discipline for the body to do its best and physical fitness is a benefit for spiritual progress. If your knees are out of shape, it’s harder to pray. Episcopalians especially need to be in shape for a service that calls for physical involvement. Lots of churches you can go to just let you sit, but this isn’t one of them. We believe not just in the resurrection of the body but the involvement of the body.

Spiritual discipline and physical discipline go together. When you hear of athletes being killed while drag racing and being arrested for rape and assault you know there’s an aspect of their training that’s been badly neglected. And when you hear of Christians without a discipline, you know there’s an aspect of their faith that’s been badly neglected.

But discipline is something we know about and not just from athletics. It’s something we give more attention to today than maybe ever before at least in some areas. Nobody jogged when I was growing up. Not very many people dieted or even worried about their diet at all. And now – well, best selling diet books, medications, exercise machines, training programs, are everywhere. And why not? It makes sense. There’s not much you can do well without working at it whether it’s cooking or driving or gardening or managing money or raising children or doing whatever we do at weekday work.

Doing anything well takes work. It takes practice and study and discipline. There’s always a temptation to coast, of course: to put aside the books when we finish school, to put off dieting until tomorrow, to limit our physical exercise to getting into the car. But at least we now know, we do know, that we shouldn’t; that lack of exercise, lack of discipline, only creates problems. And I think it all depends on motivation, doesn’t it? I can get myself into a continuing education program if it might lead to a better job; I can work at dieting if there are clothes I really want to wear or sports I want to do or if my body is telling me there are issues that need to be dealt with.

I have to admit that I didn’t take exercise seriously until I woke up one night with a muscle spasm so severe that I couldn’t get out of bed. That was about fifteen years ago and it made me a believer in exercise and it hasn’t happened again. That’s one type of motivation. What would motivate us to pay attention to our inner life, our faith? It works, I think, pretty much the same way: sometimes we do it for the benefits we see and sometimes we get scared into it. Some of us find that a spiritual discipline enhances our life, makes the day go better, helps us be the kind of people we want to be, some of us get a sudden shock through a serious illness or death of a friend or similar crisis. But probably most of us, most of the time, yield to the terrible tendency to coast, to get to a certain comfort level and let it go at that.

I think the great majority of us probably never come close to reaching our full potential, and never make much effort even to find out what we might be missing. But here we are with a reading that reminds us – and the best part of it is that Lent is still three weeks away. So we’ve got some time to think about it and maybe make Lent this year the time when we decide to make some changes. To get some discipline and order into our life of faith. So let me ask two questions: what are we trying to do and how are we trying to do it?

What are we trying to do? Why do we go to church? What is faith all about? There are probably as many ways to express it as there are people on earth but certainly a major part has to do with purpose: why are we here, what is life for? If those questions matter, do they matter enough to spend time and effort? And if God has put us here with a purpose is it possible that doing that purpose can be accomplished in our spare time, when we feel like it, without much thought or effort?

If these are things that seem to be worth working on, then the second question is: what kinds of training and discipline are likely to be helpful? You can go right back, I think to the athletic analogy. What kind of Christian would it be who seldom came to team meetings and never bothered to check for instructions? Spiritual training, spiritual discipline, pretty obviously requires regularity above everything else. To keep focused, to keep in touch with God, to nourish a sense of relationship with God and God’s people require regular times of worship – obviously: not just Sunday, but daily times of prayer.

Grace before meals is a good place to begin. If we eat regularly and pray first then we’ll pray regularly. And if we have regular times of prayer I think we’re more likely to have a sense of God’s presence in the rest of our lives as well. Being a family doesn’t require spending all your time with each other but having regular times of being together gives you that sense of being a family, you know who you are all the time because you come together regularly and not just when you feel like it. Of course there are lots of undisciplined families that don’t spend time together don’t really care about each other and it’s obvious, anybody can see the difference.

Spiritual discipline begins with regular times of being together, with regular times of prayer and Bible study and worship. You know, the Book of Common Prayer is a kind of training manual. When it first was printed, 463 years ago, there were basically two kinds of Christians: the religious and the secular, as they called them. The “religious” were the monks and nuns who lived a disciplined life with seven times of prayer a day and the “secular” were all the rest who came to mass and celebrated festivals but had very little real understanding of their faith. What Thomas Cranmer, the Archbishop of Canterbury, did was to devise a prayer book intended to provide a spiritual discipline, a religious pattern of life, for everyone. He took the seven old monastic times of prayer and combined them into two services Morning Prayer and Evening Prayer in the faith that that would give every Christian a framework for living that would keep them close to God. Twice a day they would hear the Bible read and say the psalms and prayers and it would center their lives. The clergy were required to do it – but what happened of course was that it mostly stopped there. Morning and evening prayer became very popular Sunday services, but that wasn’t the idea. The idea was a daily pattern of life. The new Prayer Book tries again by taking those two services and whittling them down much further into four very short services printed on one page each that can be read in about three minutes. Can you imagine what a difference it would make if every member of this parish, every Episcopalian had a prayer book beside the bed, on the desk at work, and used those forms of prayer regularly? Suppose we turned to God that often, suppose we prayed for each other that often, suppose we remembered who we are and who loves us that often. To use the sports analogy one more time, it might make the difference between winning and losing, being a winning team or a losing team, losing or winning the prize of life God offers.

Christopher L. Webber

Christopher L. Webber