Why Do We Do What We Do?

This sermon was preached at`St Paul’s Church Bantam Connecticut on February 13, 2011 by Christopher L. Webber.

The New York Times bestseller list has two kinds of nonfiction: a general category, mostly history and biography, and a second category called “Advice, How to, and Miscellaneous.” “How to” books make up most of the list. Some of the frequent leaders are books on taxes, and cooking, and diet. At the top of the “How to” list this morning – – over three years on the list – – is “The Five Languages of Love,” subtitled “how to communicate love in a way a spouse will understand.” Perfect for Valentine’s Day!

The “how-to” book is is an old, familiar, American phenomenon. We are a nation of doers. If things aren’t right, we want to change them. And we have this pervasive idea that if we just knew more about it, we could solve any problem. Through the years, religious books have often been at the top of the “how to” list. You may remember one called “The Power of Positive Thinking,” and more recently one called “The B (happy) Attitudes.” This week there’s one that combines religion and diet called “Made to Crave: a Scripture-based aid to following a diet.”

How to make God work for you: it’s an age-old search. And all too many of us, even if we’ve outgrown it ourselves, try to push it on our children. I’ve heard it a hundred times: “I want little Suzy to be in the Sunday school because I think it’s good for children to learn about God and how to behave and get some ethics.”

Christianity is often cheapened into a self-help program, a self-improvement program. But Christianity is not primarily an ethical system nor can you simply teach behavior. Children are not dogs to be trained; they are people to be loved. Behavior is not the point of Christian faith. It’s a byproduct at best. The church is here not so much to teach children as to love them.

Do you know that Sunday schools were only invented about 100 years ago, and in America, and only then to serve children whose families were unchurched? It’s only very recently, two generations, maybe three that the idea took hold that churches should teach Christianity to children in separate classes. And it happened, I think, for the same reason that schools took over so much else that used to be a family responsibility: a feeling that families were failing to do the job, and the notion that the world could be saved by schools, that education could save the world.

But it’s interesting to notice that in the Episcopal Church, about 75 years ago, a counter movement began with the growth of the “Family Eucharist” or “Parish Eucharist.” We still bought in to the general belief in Sunday school, though we tended to call it Church School, but church-school-with-Eucharist. Somehow we knew that there was more to learning and teaching; that Christian faith could not be reduced to a classroom experience. And especially Christian education can’t be reduced to a matter of good instruction.

Why do we do what we do?

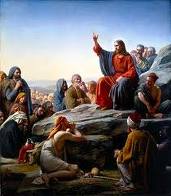

In this morning’s Gospel, we have a part of the sermon on the Mount which we are reading for several weeks, in which Jesus seems to be teaching his disciples how to behave;

“You have heard that it was said to the men of old, you shall not kill; and however kills shall be liable to judgment. But I say to you that everyone who is angry with his brother shall be liable to judgment. . . ”

“You have heard it said,” Jesus says again and again, and then he goes on, “but I say. . . .” and what he says is beyond any possibility of doing: “Do not be angry – – do not desire – – do not be limited by law but be unlimited in love.

Down through the centuries scholars have argued, “Did he mean it? Did he have in mind an impossible utopia or did he expect the kingdom to come in his lifetime and was he condemning us all to hopelessness until then? Wait until next week when we hear the end of this section and Jesus says, “Be perfect, as your father in heaven is perfect.”

Be perfect! Is that the gospel? Is that Good News? Are we really to teach our children a way of life we haven’t even tried and can’t follow ourselves? Or is Christian behavior like the 55 mile an hour speed limit: a swell idea as long as nobody really expects me to accept it?

But I believe we miss the point when we look at Christianity as primarily a standard of behavior, a system of ethics. That trivializes something intended to be far more revolutionary than just being nicer to others. These commands are serious and, yes, they are meant for us. But if we are called to be like Christ, called to perfection, then we have only two alternatives: to fail in a futile effort to do it ourselves, or to die to self and let Christ in us remake us in his image. I think that is the goal: Christ in us. And that is what baptism is all about, what the Eucharist is all about, what prayer is all about. It’s about dying to self and letting Christ, live in us. And as that happens, behavior will take care of itself. We will become a new person and act like that new person.

I happened to have a talk show on the car radio one day and the subject was alcoholism. A woman called in and said she was living with a man she loved a lot, but he was alcoholic and would get depressed over something, and get drunk, and beat her and her child. “Get out!” said the talk show host. “Go to Al-anon. Hear about it from people who have been there. But you can’t change him. He has to change himself.” There was dialogue back and forth and finally the woman said, “Well, all right, but what about him? Should he go to a meeting?” And the talk show host, a psychiatrist, said, “Of course he should go to a meeting. He should stop drinking. But should is a meaningless word. You do what you have to do.”

“Should is a meaningless word. You do what you have to do.”

Well, how often have you and I said, “I know what I should do, but . . . ” Haven’t you said that? I know I have. What controls your life: “should” or something stronger? “You do what you have to do.” Exactly right. And what we have to do is what we are, what’s in us, our inner nature. Which doesn’t mean we are simply helpless victims of our genetic inheritance and environment, that we “can’t help ourselves” – – a kind of “no-fault” ethics.

No, it means that we need to concern ourselves not so much with the rules we learn as with the relationships we form, and with the environment we choose to live in; not so much with what guides us from the outside as with what shapes us from the inside, that in-forms us, not so much with what relationships we create as with what relationships re-create us.

Why do we do what we do? “A bad tree,” Jesus said, “cannot produce good fruit.” You can say “should” to it all you want; it won’t happen. What matters is the soil and the rain and inherited genetic traits that form that tree over the years from within. So too we may hear sermons that tell us “should” but they will have no affect on us unless we have found a source of life in the Eucharistic community that enables us to do what we know we should do.

Jesus said, “Do this,” and he took bread and said, “This is my body.”

Why do we do what we do? Because Christ in us so shapes our hearts and minds that we love what he shows us and that makes “should” a meaningless word.

Christopher L. Webber

Christopher L. Webber