A Warning – and Hope

A sermon preached by Christopher L. Webber at St. John’s Church Washington, Connecticut, on September 26, 2010

They say that every parable has just one point and today’s story certainly only has one that gets our attention. But I suspect you won’t like it so I’m going to try to squeeze out one more.

Here’s point one: rich is bad and poor is good, at least in the long run.

Have you ever stopped to think how unreligious this parable is? I mean, we are told absolutely nothing about the rich man or the poor man in terms of faith. We don’t know whether they went to synagogue every Sabbath or made a pledge or said their prayers or any of that. We just aren’t told. Apparently it doesn’t make any difference. The rich man was rich and therefore he went to hell. The poor man was poor and therefore he went to heaven. Nothing else seems to matter. Look at the other readings and it’s still the same message: if you’re rich, you’re in trouble.

Now, we may not think this applies to us because we don’t perhaps think of ourselves as rich. We never played third base for the Yankees or ran the World Wrestling Federation or dreamed up Microsoft or Facebook after dropping out of college. So we’re not rich. Compared to people like that, maybe not. Compared to the Wall Street and Hollywood and sports personalities, we may be in the same boat as Lazarus, most of us. But compared to most of the population of the world, we are a whole lot more like the rich man. Everyone of us has a radio and television and running water and electricity and the rich man in the parable had none of these things, nor did Caesar Augustus, nor do most of the world’s population today. People in Haiti today will launch out across shark infested waters in a leaky boat just to get here illegally. People from China will hand over their life savings and mortgage their future to bandits to get here and take a job working twelve hours a day at substandard pay. Mexicans will risk being shot on the border or dying of thirst in the desert to take jobs no American will do. By world-wide standards everyone of us is rich beyond their wildest dreams and we are as indifferent to their needs as Dives was to Lazarus.

I don’t like this parable myself. It makes me very nervous. I may tithe to the church and contribute to Episcopal Relief and Development and the Bishop’s Fund for Children and take part in walks for all kinds of good causes and all of that – and still live very comfortably in a world where most people are hungry. Short term, that’s fine. Long term, the parable doesn’t offer me much hope.

Now, that’s very depressing, and the gospel is supposed to be good news. So let me see if I can squeeze some good news out of it and find a second point somehow.

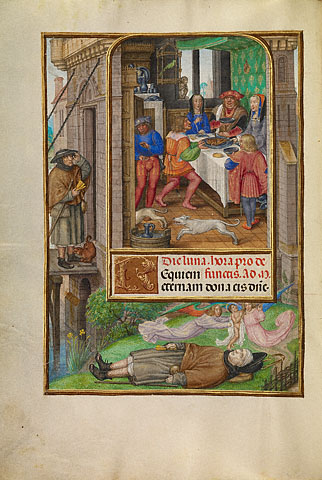

I might begin with the fact that the rich man in the parable is grotesquely rich: he wears purple and fine linen and feasts sumptuously every day. The language indicates an extravagant feast, conspicuous consumption. And whether he tossed his crumbs to the poor man, we never hear but it seems unlikely. He didn’t care. Just didn’t care. Even in hell, his first thought is for his own comfort; his second thought is to get Lazarus to wait on him; and his third thought is for his brothers – finally, for someone else. Maybe there’s some small gleam of hope for Dives at last. But we, I hope, are not as hopeless as Dives: not totally self-indulgent, not completely indifferent to the needs of others. We do give, maybe not as much as we could, but something. And we give of ourselves in some ways. And we, unlike Dives brothers, are here today to hear Moses and the prophets and the Gospel as well. So maybe there’s some small hope for us after all.

But all that is still about point one: to be rich is – if not fatal, at least very dangerous. We live in a world and society increasingly, dangerously, divided between rich and poor. The poorest of us can still help someone else, can help make a difference. We heard last week about the love of a God who cares about each and everyone. That’s our calling also – in fact our privilege to share in Christ’s ministry of love. Maybe that counts for something. That’s the silver lining on Point One.

Is there a second point? I think there may be one more thing we should notice. Way at the end of the story, when Dives finally begins to be concerned about someone else, he wants to do something about his brothers because they apparently are headed for the same place where he is, and the question is, how to send them a message. That’s an interesting question to think about because if there’s one thing that frustrates Christians – Episcopalians especially – it’s this: that we don’t seem to knowhow to get our message out. There’s a gospel we’ve heard about love unlimited and everlasting life. Wouldn’t you think people would rather hear about that than the stock exchange and the war in Afghanistan and the new season on television? But, you know, they wouldn’t!

I can remember a day when the New York Times would report on Monday what some preacher or other said on Sunday. Not any more. That doesn’t sell papers. Nowadays the church gets in the news only if there’s a scandal.

How can we get our message out, get people’s attention? Now Dives is smart. He’s made a lot of money in his life and he knows how to get people’s attention. To get his brother’s attention, he knows, won’t be easy – but maybe if someone comes to them from the dead – if they wake up in the middle of the night and there’s Lazarus, ghostly white, telling them in sepulchral tones that they’d better get with it, maybe, just maybe, they would shape up while they have time. But Abraham has been around awhile and he knows better. Look, he says, the Bible gets read in the synagogue every Sabbath. The message is there. All they have to do is pay attention. But Dives knows his brothers and he thinks Abraham has missed the point. “No, Father Abraham, you don’t know my brothers; they’re reading the stock market report and checking their bank accounts and ordering in cases of vintage wine; it’s going to have to be something special that wakes them up.” Abraham still knows better. “If they don’t hear Moses and the prophets, neither will it make any difference if someone comes to them from the dead.”

And, of course, Christians hearing that know that he’s right. We have a messenger from the dead and there’s hardly anyone who hasn’t heard about it. But life goes on. Most people still have higher priorities. In fact, every year, in every church, we put on a spectacular performance for Easter – music and flowers and all the trimmings – and attendance doubles and we proclaim the resurrection. And the next Sunday it’s right back to normal or even below. If they hear not Moses and the prophets neither will they be persuaded even though Jesus rose from the dead. Abraham is right. Hearing the gospel is a long, slow process of growth. Conversion is seldom dramatic or showy.

There are churches today that try the showy approach: there’s one out on Route Seven you may have heard of: the kind of place where they seat you theater style, and throw the words of the hymns on the screen, and entertain the congregation with professional rock bands and the whole bit. And people do come, but do they hear the gospel? Is their life really changed? Or have they just found a convenient way to feel good about themselves?

We’re into Christian education season and any church school teacher can tell you it’s slow, patient, sometimes discouraging work. You won’t see results overnight, or maybe for years and years. But our task is to stick with it – not to scare people to death or shake them til their teeth rattle or just entertain them either – our job is to pay attention to Moses and the prophets, to the Bible, to the Gospel: to listen, day by day and week by week and grow the way all life does, slowly, steadily, patiently toward a final harvest. I think that’s the second lesson in this parable. For all the business about the flames of hell and the bliss of heaven, that, in the end, is irrelevant. If people respond out of fear they’ve missed the point anyway. Real change is slow. Real growth is slow. And we need patience, we need to stick with it. We’re in it for the long haul. That’s point two and I think it’s there and we need to hear it.

The parable deals with wealth and poverty, yes; don’t forget it. Point One. It also deals with eternal values, eternal life, not short term benefit. Point Two. This life needs to be seen and lived in that perspective. In that perspective, wealth is a needless weight and compassion and patience and faithfulness are the true wealth, the wealth that will last forever.

Christopher L. Webber

Christopher L. Webber